Rabbi Yedidya (Julian) Sinclair, Director of Education, Jewish Climate Initiative, and Hazon Rabbinical Scholar

Recently I was asked an interesting question by an Israel environmental leader.

“I was a bit surprised and somewhat dismayed,” he began, “to find out that the date chosen for the Copenhagen Planning Seminar was also Tisha B’Av.”

A bit of background for the uninitiated:

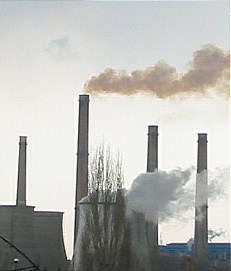

1. The Copenhagen Summit in December is a gathering of world leaders that aims to bash out a successor agreement to the Kyoto protocol that will limit CO2 emissions going forward. It is widely seen as a critical moment in the global effort to address climate change.

2. The particular Seminar spoken about here is a gathering of Israeli environmental NGO’s that will propose an Israeli position for the Copenhagen Summit. Israel has not so far taken an official line on global warming. That is probably about to change. The new environment minister, Gilad Erdan, is one of the very few in recent years not to see the appointment as a consolation prize for not receiving a “real” ministerial job.” Erdan gets it. He understands that the environment really matters. The Tisha B’Av seminar includes a meeting with him.

2. The particular Seminar spoken about here is a gathering of Israeli environmental NGO’s that will propose an Israeli position for the Copenhagen Summit. Israel has not so far taken an official line on global warming. That is probably about to change. The new environment minister, Gilad Erdan, is one of the very few in recent years not to see the appointment as a consolation prize for not receiving a “real” ministerial job.” Erdan gets it. He understands that the environment really matters. The Tisha B’Av seminar includes a meeting with him.

3. Tisha B’Av is the saddest date of the Jewish year. It is a fast day marked by deep mourning for the destruction of both Temples, the massacres and dispersions that followed and the ensuing 1800 years of exile from our country.

My environmental leader friend (who is himself Jewishly observant) was troubled by the choice of date for this meeting. While he knew that the decision was made in good faith, with good will, and certainly without any intention to inconvenience observant Jews, he wondered whether it might not be “singularly inappropriate to have the meeting on that day?” Or possibly, he continued, there was a “meaningful connection that could be made between Tisha B’Av and climate change?”

“It’s an interesting one”, I wrote back to him.

“On the one hand, holding the event on Tisha B’av certainly makes it hard for anyone who is halakhically observant to come, at least in the morning. It’s prohibited to do work until noon on Tisha B’Av and even to greet anyone a sign of our utter desolation on that day (which would pose problems for how to behave in a meeting.) There’s a strong custom of spending the whole morning in synagogue. That’s before you even start thinking about the effects of not eating and drinking all day in the middle of summer in Tel Aviv. So, on grounds of inclusiveness it’s not exactly an ideal choice of date.”

“On the other hand”, I mused, “maybe there was something singularly appropriate about the choice of date…” Talking with people about this since, I realize that it might in fact be true in more ways than I thought.

Firstly, some have drawn an analogy between the burning of the Temple and the ecological threats of today. As Rabbi Arthur Waskow writes, “This memory of the burning of the Temple comes when scorching winds blow across the Middle East, when forest fires blaze, when grassy savannahs shrivel in the drought brought on — in our generation — by global heating. It is as if the burning of the Temple is a miniature version of the scorching of our planet.”

Waskow calls for people to fast on Tisha B’Av this year, or at least to fast from consuming gasoline and beef, (two of the biggest causes of greenhouse gas emissions)- a call we strongly endorse.

Secondly, as Dr. Michael Kagan of Jewish Climate Initiative pointed out, Tisha B’Av is the day on which it was decreed that the Jews would wander in the desert for 40 years of exile as a punishment for the sin of the spies, who shunned the goodness of the Land of Israel. In the terrible words of the Talmud:

“Rabbi Yochanan said that day (when the decree was made) was the eve of Tisha B’Av. The Holy One said, “you have wept for no reason. I will fix on this day weeping throughout the generations.” (Talmud Bavli, Ta’anit 29a).

According to Rabbi Yochanan, the people’s acceptance of the spies’ slanders and their groundless weeping about the problems they anticipated in the Land of Israel was a kind of original sin. Because that generation refused the challenge of entering the land and implicitly preferred exile, Tisha B’Av was marked out forever as a day of weeping for exile from our land.

Only now are we starting to repair the effects of our longest exile. We here in Israel are painstakingly learning how to live here once again. We have made many mistakes, in water use, forestry and city planning, but through the remarkable efforts of Israel’s environmental movement we are relearning how to bear responsibility for our natural environment. How uncannily appropriate that a meeting at which the reborn State of Israel’s Minister of the Environment will be asked to rise and take some responsibility for the earth’s greatest environmental challenge should be inadvertently scheduled for Tisha B’Av.

And there is another level to this too, To appreciate it, let’s first note that Tisha B’av is one of several fast days in the Jewish calendar. In their purpose, these days fall on a spectrum between Teshuva repentance, and mourning. These purposes are not the same. Teshuva is about examining our lives individually and communally asking ourselves what needs to change and resolving to be better from now on.

Mourning is about experiencing and grieving for a loss. These purposes may overlap but they are not the same. Yom Kippur is a fast of Teshuvah but not a day of mourning. On the other hand if someone close to us dies, our main response is one of mourning, not of Teshuva.

As Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik points out, Tisha B’Av itself is a fast of mourning and not of repentance. We don’t try to fix anything on Tisha Bav, but to experience the magnitude of the catastrophe that befell us. We sit on the floor and read tragic elegies for Jewish suffering. We weep, cry out and come face to face with the horrors of the destruction and everything that followed from it; the blood running knee deep in the streets of Jerusalem the massacres the exiles, the expulsions, the inquisitions, the pogroms and the gas chambers. We remember that we are a people that has seen the worst; we have been in the deepest pits of hell and on Tisha B’av we revisit those places.

And we’ve also come out of the deepest pits of hell, with a fierce commitment to love and to cherish life.

On Tisha B’Av, the Midrash says, the Messiah will be born.

This Tisha B’Av, it is to be hoped, the State of Israel will be take a significant step towards loving and cherishing all of life on earth.