by Chelsea Stephens, Teva, Hazon

Parashat Shelach

When we pulled up, the gate was locked.

We didn’t have anyone’s number. We didn’t really know if we were in the right spot.

Luckily though — for me and the two co-workers (and best friends) I pulled up with — there were no Nephilim in the distance, or enemy armies in the hills. Still, as we arrived for our first day on the job as summer garden specialists at Camp Twelve Trails, I felt a bit like the twelve spies sent by Moses to scout the Land of Israel.

Wait, like who? Ok – so to recap this week’s Torah portion (Shelach), Moses sends twelve scouts into Israel. Forty days later, they come back with two conflicting reports:

- The land is fertile and beautiful, BUT …

- It’s inhabited by Nephalim — the bastard children of antediluvian human-angel mating. How exciting! (bet you don’t remember that story from Sunday school)

As I first looked out over the camps fields and untended gardens, I felt similar conflict. I was at once scared to be leaving my home for the summer, apprehensive about the work to be done, but excited at the potential, and enlivened by the challenge.

Twelve Trails is a new day camp, a bus ride away from the Upper West Side, run by our friends at the YM&YWHA of Washington Heights & Inwood. Through our Teva program, Hazon is partnering with Twelve Trails to help build their garden program and Jewish content as they continue growing into their second year.

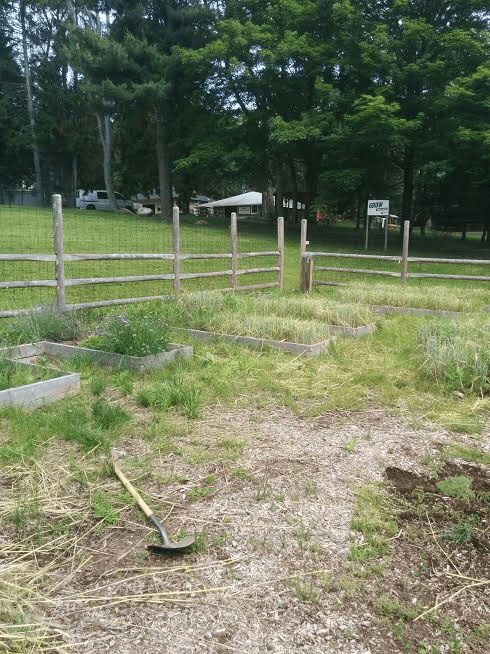

Forming a summer successful summer camp program is not so unlike the scouts’ adventure — an early wave of community building. Ok, maybe they had a few more challenges. Forming a summer camp in a pleasant NYC suburb isn’t the same as forming a nation in the unyielding desert … but maybe, in some ways, it’s close. Like the scouts, I was struck by the camp’s natural beauty — all tall oak trees and winding creeks. Sure, it’s hardly the wilderness, and seeing the weed covered garden plot left over from last year hardly felt like entering the land of milk and honey. But I’m excited to be at such a new organization. It means being able to bring a lot of myself, be creative with programming and build a camp culture that could last for years — much like the first generations of Israelites entering a new land full of both fertile hills and giant obstacles (literally).

So what can we lessons can we learn about community building from this week’s parsha? As the story unfolds back at the camp, two lessons emerge.

First, a fledgling community must have some good faith in the future. Upon hearing the scout’s conflicting reports, the citizens of the Israelite camp choose to focus on the negative. Instead of trying to be a bit optimistic, they mumble and whine about how they were better off as slaves. Things don’t get better from here. The Israelite camp experiences what we might call the first pogrom, when Amalek, a not so nice tribe of hill warriors, ravages the camp. Bnai Israel is really unhappy — but then, I can’t really fault them. Despite the constant flow of manna, life is hard in the desert. It would be nice to finally feel at home somewhere.

At this point in the Torah, G!d is not being subtle with doling lessons. Later in the parsha, for example, He sentences a man to death-by-stoning for gathering wood on Shabbat.

I’ll touch on that later.

I think the fate Hashem deals to the people of Israel is actually worse. For being a bit displeased with the current state of affairs, they are sentenced to never enter the Land of Israel — the land they left Egypt for and the only home they might ever know.

I find this terribly depressing, and one of the hardest parts of Torah to reconcile. Its understandable that this beaten down bunch of ex-slaves would have a hard time being optimistic, but maybe that’s the lesson G!d is trying to teach future generations by punishing the Israelites: Even though everything seems tough and completely overwhelming, you have to focus on the bit of faith that it will all turn out ok.

Maybe fulfilling our desert wanderings’ worst nightmares is an ironic way to get that across, but point taken. I wouldn’t be the first one to propose that forty years in the desert was Hashem’s way of teaching our ancestors — and the Jewish people throughout history — to have a positive attitude.

Like the Israelite scouts looking out over enemy encampments and giant angel brood, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed as I looked out over our untended, weed filled garden patch; our weeks worth of curricula to write; all the new people to meet and systems to learn. The feeling of “this is too big a job with too little time” hung in the air between us for the whole first day. Our own Nephilim loomed from the hills — visions of failed crops and unhappy campers. Our conversations began to echo the mumbling and whining, the uneasy glances and apprehension of Bnai Israel.

The second day, we went to the plant nursery. With our truck filled with tools and vegetable starts, we drove through the open gates and broke ground early in the morning. Luckily for us, Hashem had not cursed us to 40 years on the outside, but instead, blessed us with a cool sunny day and irrigation system that still worked from last summer. As the sun set, we had six beds planted and a few new friends from among out co-workers.

Bnai Israel was forced to take a hard lesson in Emunah, in faith that the future would be good and that the land G!d had given them would provide. Hopefully, our faith in the land and in each other will be just what we need to build our Camp community.

So, now for lesson number 2.

What does it mean to sentence a man to death, by stoning no less, for collecting wood on Shabbat? It’s a harsh punishment — and, most interestingly, comes out of chronological order with the rest of the Parsha. So, whoever’s divine hand wrote our Torah thought that this little episode should be told right after our lesson on optimism.

So why here? It goes back to building community. Earlier we learned that a growing spiritual community needs optimism, safety and sustenance. Here, we learn a growing community also needs boundaries.

Hashem had given the Ten Commandments two weeks earlier and the Jews were already breaking them. I’m reminded of a teaching tip I learned years ago: “it’s easier to loosen up later than it is to tighten up later.”

Everyone who’s ever had a group of unruly kids knows that if firm boundaries aren’t set on day one, it’s one thousand times harder to backpedal and set them on day two. After a habit of rule breaking has already been established, it’s hard to get people working together.

So within Parashat Shelach, we get two lessons on building a new community. First we must be optimistic; second, we must have clear and enforced boundaries.

I think this applies easily both to our building the camp community and in our own lives throughout the summer. In order to make this project work, we’ll need to hold each other accountable. We’ll need to decide the kind of values our camp culture needs to uphold, and stick to them. But more importantly, we’ll need to look out over fledgling camp community and believe that we can make it blossom.

Chelsea Stephens is the Teva JOFEE Fellow at Hazon. She is also a fiber arts enthusiast and aspiring forest elf, originally from the great state of New Jersey, with experience in farming and nature-based Jewish education. Read her full bio here.

—

Editor’s Note: Welcome to D’varim HaMakom: The JOFEE Fellows Blog! Most weeks throughout the year, you’ll be hearing from the JOFEE Fellows: reflections on their experiences, successful programs they’ve planned and implemented, gleanings from the field, and connections to the weekly Torah portion and what they’ve learned from their experiences with place in their host communities for the year. Views expressed are the author’s and do not necessarily represent Hazon. Be sure to check back weekly!